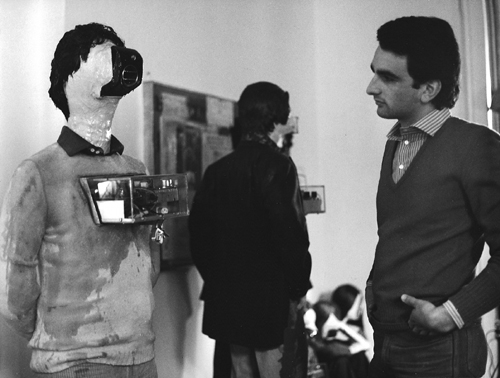

The artistic genius Kienholz crossed through the American artistic culture from the 60’s to today, leaving a distinct and unequivocal mark of transgression and innovation. In the 60’s and 70’s he wasn’t that well-liked by the artistic establishment surrounding the great galleries of New York. His dedication to social problems, the pacifist struggles, the criticism of the Vietnam War  and his support of the battles for civil and social commitment

left him in opposition to that part of American art, Pop art, which was supported by mass communications and the heart of American power. Keinholz used to love reminiscing about rejecting Leo Castelli, the powerful Newyorkian art gallery manager that wanted him among the “pop artists” of his gallery. The artist’s works frequently sparked violent controversies because they wedged into the deep and painful wounds of a society marked by countless contradictions. One of his works in particular, “The Portable War Memorial”, an anti-Vietnam war fresco depicting Marines planting a flag not upon conquered soil, but on a fast food table instead, provoked quite a bit of controversy. One evening at a friend’s house in Los Angeles, I too discovered the part of the American artistic world that didn’t care that much for Kienholz:

and his support of the battles for civil and social commitment

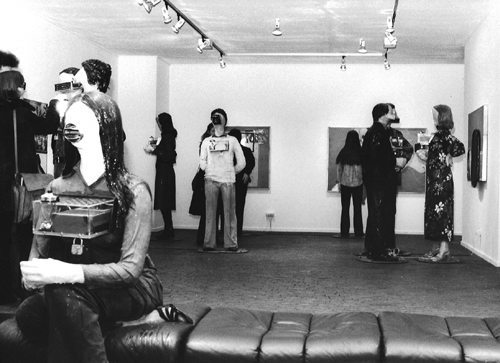

left him in opposition to that part of American art, Pop art, which was supported by mass communications and the heart of American power. Keinholz used to love reminiscing about rejecting Leo Castelli, the powerful Newyorkian art gallery manager that wanted him among the “pop artists” of his gallery. The artist’s works frequently sparked violent controversies because they wedged into the deep and painful wounds of a society marked by countless contradictions. One of his works in particular, “The Portable War Memorial”, an anti-Vietnam war fresco depicting Marines planting a flag not upon conquered soil, but on a fast food table instead, provoked quite a bit of controversy. One evening at a friend’s house in Los Angeles, I too discovered the part of the American artistic world that didn’t care that much for Kienholz: at The Art Show 1963-1977, a work of Kienholz displayed for the first time at the Beabourg Museum of Paris was so vehemently criticized by the pop-artist Claes Oldenburg with such blind spite that he would have deserved much more than just a wisecrack in response from me.

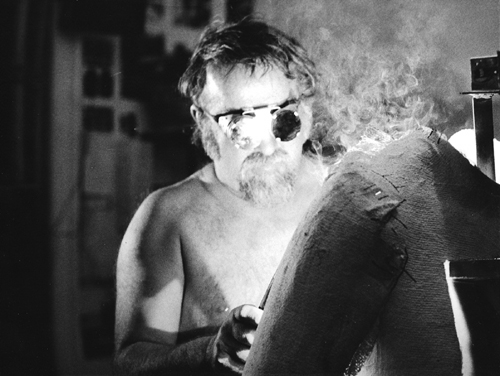

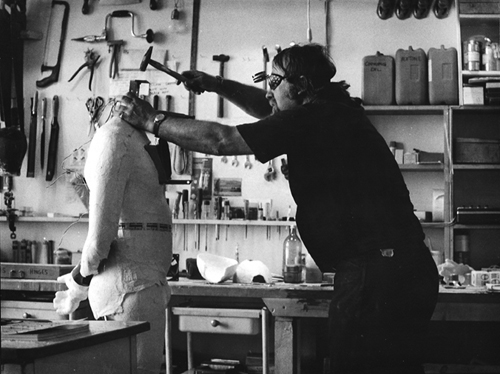

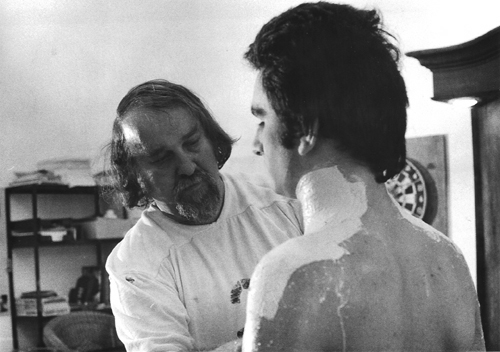

Kienholz was born in Fairfield, Washington in 1927, on the very northwestern border of the United States to a family of farmers. His first business in Los Angeles in the 50’s was to create work relations with other radical artists and to involve the general public in self-managed galleries. His first works were generally composed of junk and “human experience remains”. In 1956 he founded the NOW Gallery in Los Angeles and in the following year The Ferus Gallery with Walter Hopps. In those years he was constantly on the go to organize artistic events that “got people involved” and weren’t just “consumed” by the public. Kienholz, in that period of extreme poverty, was forced to do all kinds of odd jobs: he told me that he would ride around Los Angeles in a truck with the word “Expert” plastered on it with these huge letters. “And what is an artist?” he would ask, remembering those years with a smile. “Is he not an ‘Expert’…?” It was just his poverty that kept him from buying the materials needed to create the great works that led him to conceiving one of the most extraordinary inventions of modern art, the Concept Tableaux.

at The Art Show 1963-1977, a work of Kienholz displayed for the first time at the Beabourg Museum of Paris was so vehemently criticized by the pop-artist Claes Oldenburg with such blind spite that he would have deserved much more than just a wisecrack in response from me.

Kienholz was born in Fairfield, Washington in 1927, on the very northwestern border of the United States to a family of farmers. His first business in Los Angeles in the 50’s was to create work relations with other radical artists and to involve the general public in self-managed galleries. His first works were generally composed of junk and “human experience remains”. In 1956 he founded the NOW Gallery in Los Angeles and in the following year The Ferus Gallery with Walter Hopps. In those years he was constantly on the go to organize artistic events that “got people involved” and weren’t just “consumed” by the public. Kienholz, in that period of extreme poverty, was forced to do all kinds of odd jobs: he told me that he would ride around Los Angeles in a truck with the word “Expert” plastered on it with these huge letters. “And what is an artist?” he would ask, remembering those years with a smile. “Is he not an ‘Expert’…?” It was just his poverty that kept him from buying the materials needed to create the great works that led him to conceiving one of the most extraordinary inventions of modern art, the Concept Tableaux.

A leader in the development of several aspects of conceptual art, he described every single one of his works in a type of film script in minute detail. The collector could only purchase “the script” or the creation of the work in sculpture form for just the cost of the material and hourly wages of the artist, about the average wages of plumbers, carpenters and electricians in the area of Los Angeles. Now these works, the “Tableaux vivant are worth millions of dollars and are property of the most important museums in the world. At the beginning of the 70’s, after his memorable participation in the Kassel’s Documenta 5 with Five Car Stud, a tableaux vivant against racism, and a great itinerary of shows in the principle European museums supervised by Pontus Hulten, Kienholz became consecrated as one of the most important figures of modern art. In 1973 he transferred to West Berlin on invitation by the DAAD, a German cultural organization. It was in that year, thanks to a presentation by the artist Wolf Vostell, that I met him. After the show that I organized in 1974, Kienholz began to discover Italy and above all Parma, which left him “contaminated”, as he would say. At first he refused to visit the museums, the monuments and the churches because he wanted to preserve a “pure outlook”: he didn’t want for his artwork to be influenced or conditioned by distinguishing traits of other cultures. Only after I insisted on numerous occasions did he finally begin approaching Antelami’s Romanic sculptures. He suspiciously observed the sculptures in the Baptistery in Parma and then, with an air of relief whispered to me, “Superb!” That “contamination” continued with opera:

A leader in the development of several aspects of conceptual art, he described every single one of his works in a type of film script in minute detail. The collector could only purchase “the script” or the creation of the work in sculpture form for just the cost of the material and hourly wages of the artist, about the average wages of plumbers, carpenters and electricians in the area of Los Angeles. Now these works, the “Tableaux vivant are worth millions of dollars and are property of the most important museums in the world. At the beginning of the 70’s, after his memorable participation in the Kassel’s Documenta 5 with Five Car Stud, a tableaux vivant against racism, and a great itinerary of shows in the principle European museums supervised by Pontus Hulten, Kienholz became consecrated as one of the most important figures of modern art. In 1973 he transferred to West Berlin on invitation by the DAAD, a German cultural organization. It was in that year, thanks to a presentation by the artist Wolf Vostell, that I met him. After the show that I organized in 1974, Kienholz began to discover Italy and above all Parma, which left him “contaminated”, as he would say. At first he refused to visit the museums, the monuments and the churches because he wanted to preserve a “pure outlook”: he didn’t want for his artwork to be influenced or conditioned by distinguishing traits of other cultures. Only after I insisted on numerous occasions did he finally begin approaching Antelami’s Romanic sculptures. He suspiciously observed the sculptures in the Baptistery in Parma and then, with an air of relief whispered to me, “Superb!” That “contamination” continued with opera:

one evening we went to see ”Rigoletto” on its fourth night of performance, directed by a young American conductor. It was an extraordinary evening. Kienholz was deeply struck by it all. Shortly afterwards he wrote about it on a catalogue of one of his shows at the Beaubourg in Paris: “ Verdi on in the Parma Opera House, in a private box full of sophistication and wine and with such a demanding audience that it can’t be described with just a few words”. Perhaps Kienholz found a kind of connection between opera and his own works: The Tableaux Vivant” were created from faraway memory of plays, costumes and stop-action scenes that Kienholz saw in the country churches and drawing rooms of rural farms. And in these plays, just as in opera, things such as one’s feelings and passion and man’s eternal dramas were described. A few months later we were driving through the vast stretches of Idaho farmland. The background music was, as usual, country-western. Kienholz looked at me and changed the cassette that was on with a smile. He began to sing softly along, happy as he could be, in this made-up language of more sounds than words, with an opera: it was Rigoletto. On that infinite strip of highway separating enormous stretches of cultivated farmland as far as the eye can see, perhaps he had revealed a sneak preview of something in musical form. It was right in Idaho, a northwestern, wild, agricultural state where Kienholz had been living for years after the Berlin period.

one evening we went to see ”Rigoletto” on its fourth night of performance, directed by a young American conductor. It was an extraordinary evening. Kienholz was deeply struck by it all. Shortly afterwards he wrote about it on a catalogue of one of his shows at the Beaubourg in Paris: “ Verdi on in the Parma Opera House, in a private box full of sophistication and wine and with such a demanding audience that it can’t be described with just a few words”. Perhaps Kienholz found a kind of connection between opera and his own works: The Tableaux Vivant” were created from faraway memory of plays, costumes and stop-action scenes that Kienholz saw in the country churches and drawing rooms of rural farms. And in these plays, just as in opera, things such as one’s feelings and passion and man’s eternal dramas were described. A few months later we were driving through the vast stretches of Idaho farmland. The background music was, as usual, country-western. Kienholz looked at me and changed the cassette that was on with a smile. He began to sing softly along, happy as he could be, in this made-up language of more sounds than words, with an opera: it was Rigoletto. On that infinite strip of highway separating enormous stretches of cultivated farmland as far as the eye can see, perhaps he had revealed a sneak preview of something in musical form. It was right in Idaho, a northwestern, wild, agricultural state where Kienholz had been living for years after the Berlin period.  On the banks of a small lake, immersed in the midst of acres and acres of pinewood forest, he had built a Canadian style log cabin for himself and three of his children with his own hands. He had also built a big private museum: The Faith and Charity in Hope Gallery, a play on words after the name of the village where the museum is situated, Hope. But the museum wasn’t dedicated to his own work. Kienholz had wanted it to exhibit other artists.

It was truly a curious sight to see cowboys and farmers at the inauguration of exhibits by Bacon, Giacometti and other great masters worthy of great museums. In the past few years he had rarely returned to Europe: it was no longer the moment to be at the Flohmarkt in Berlin to look for objects for his works. The 70’s were over for the Steinplatz Hotel: there were no longer artists, sculptors, and musicians from all over the world to help the artistic culture survive during the cold war. An era was over: maybe Keinholz had sensed that in that moment of artistic, social and political confusion he had to rediscover the values, connected to the land and social way of life of America, that had led him to the creation of some of the greatest works of art of that century. “Anyway, it’s always the others who die…” said Duchamp. It’s true. For artists, for great artists such as Edward Kienholz, it’s really true.

On the banks of a small lake, immersed in the midst of acres and acres of pinewood forest, he had built a Canadian style log cabin for himself and three of his children with his own hands. He had also built a big private museum: The Faith and Charity in Hope Gallery, a play on words after the name of the village where the museum is situated, Hope. But the museum wasn’t dedicated to his own work. Kienholz had wanted it to exhibit other artists.

It was truly a curious sight to see cowboys and farmers at the inauguration of exhibits by Bacon, Giacometti and other great masters worthy of great museums. In the past few years he had rarely returned to Europe: it was no longer the moment to be at the Flohmarkt in Berlin to look for objects for his works. The 70’s were over for the Steinplatz Hotel: there were no longer artists, sculptors, and musicians from all over the world to help the artistic culture survive during the cold war. An era was over: maybe Keinholz had sensed that in that moment of artistic, social and political confusion he had to rediscover the values, connected to the land and social way of life of America, that had led him to the creation of some of the greatest works of art of that century. “Anyway, it’s always the others who die…” said Duchamp. It’s true. For artists, for great artists such as Edward Kienholz, it’s really true.

Giancarlo Bocchi

July, 1994